The Power of Role Models for Breastfeeding

“What you leave behind is not what is engraved in stone monuments,

but what is woven into the lives of others.”—Pericles, Ancient Greek Statesman.

Photo provided by Saron Chhem taken by her husband Mark Reibman (Cambodia)

This issue of the Breastfeeding Mother Support E-Newsletter, Vol 16, No 2, brings together stories from around the world that touch on the power of role models for breastfeeding for a mother to initiate and succeed in her journey of breastfeeding. In cultures where breastfeeding has moved away from the public eye, many women will begin motherhood with hardly, if any, exposure to a breastfeeding role model. Breastfeeding support comes in many shapes and sizes, and one key piece of this puzzle is the visually accepting, normalizing stream of breastfeeding mothers— in the news, among friends, within families, in the work place, in public places. More and more women are wanting to breastfeed, but more and more women are struggling to “know how”. We hope the stories shared in this issue motivate us to continue setting the stage for lifting mothers up with the power of breastfeeding role models.

As said so beautifully by Melissa Vickers: “When mothers are adequately supported to breastfeed, everyone—the baby, the mother, the family, the community—benefits. This kind of support, coming from many different facets of society, helps move us toward breastfeeding as the cultural norm and weaves a tapestry of support. Tapestries are both beautiful and strong, and the beauty and strength come from the diversity of types of support interwoven together. While any form of support can help a mother breastfeed her child, the synergistic effect of the tapestry makes it easier on that mother, empowering her to support other mothers.” (The 10th Step & Beyond: Mother Support for Breastfeeding. Virginia Thorley and Melissa Clark Vickers, editors. Hale Publishing Company, 2012)

—Natalia Smith and Melissa Vickers, Editors

IN THIS ISSUE

Editor’s Letter

SPOTLIGHT

Mothers’ Voices

- Following my Instincts, Nanda Gasparini (Cambodia)

- A Friend Saved the Day, Noelia Barros (Paraguay)

- At First, I also Struggled to Nurse my Baby, Hanny Ghazi (France)

- Breastfeeding is Beautiful at its Core, Ivana Cortez (Argentina)

Best Practices

- Establishing a Model Campus-Wide Breastfeeding Program in Connecticut, Michele Vancour and Chandra Kelsey (USA)

- How a Breastfeeding Initiative in Rural Kenya Changed Attitudes, Judith Kimiywe and Elizabeth Kimani-Murage (Kenya)

Family Matters

- My Experience of Supporting my Wife to Breastfeed our First Child, Jean-Marie Nkurunziza (South Africa)

- How I’m Right and My Wife Isn’t, Arthur Molloy (Isle of Man, UK)

Changemakers:

- How Working Mothers Can Be Role Models for Breastfeeding, Vania Smith-Oka (USA)

- The Dirty Truth about the Infant Formula Industry, Save the Children (Cambodia and Norway)

- Mother Nature Knows Breast. Aisling O’Leary, Louise Feehely, Nicole Clarke, and Katie Cronin (Ireland)

Children’s Corner

Honouring Breastfeeding Advocates

Stay Current: Research, happenings, and breastfeeding in the news

We Welcome your Submissions

The Breastfeeding Mother Support E-Newsletter is published twice a year by the World Alliance for Breastfeeding Action (WABA) to promote an environment of awareness and support for all mothers to initiate and sustain breastfeeding. It includes stories, new information relevant to the promotion and support of breastfeeding, and highlights efforts across the world by organizations, health workers, businesses, communities, etc. in supporting the breastfeeding mother. The newsletter helps all of us who work in breastfeeding to feel supported and appreciated in what we do and to improve how we help mothers, fathers, families and communities in breastfeeding.

We welcome your suggestions or submissions which may be any actions taken, specific work done, investigations and projects carried out from different perspectives and from different parts of the world that have provided support to women in their role as breastfeeding mothers. Submissions should be between 250 and 800 words, and should include a title and a short biography of the corresponding author (2 to 3 sentences). Please be specific in including details where relevant such as name of places, persons, and exact dates. Photos illustrating a subject specific to your submission also are welcome. Please send to gims_gifs@yahoo.com.

We reserve the right to edit every submission for spelling, grammar and clarity of content.

Please share this newsletter with your friends and colleagues. To subscribe, please email gims_gifs@yahoo.com.

The opinions and information expressed in the articles of this issue do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of WABA, the Mother Support Working Group nor the Newsletter Editors.

Role Models for Breastfeeding

Melissa Vickers

In some parts of the world, I suppose, asking a mother who her role models for breastfeeding were might be as silly as asking her who her role models were for walking and talking. Countries where breastfeeding is the norm have role models everywhere, integrated into normal, everyday life. They are a part of the accepted way of parenting, and the mere sight of a breastfeeding mother is not unusual or necessarily memorable.

In the United States and other countries where the breastfeeding rates are not as high and visual role models are not so common, the sight of a breastfeeding woman can be a lifelong image that sparks some notion of “I want to do that, too!”

I do remember the first woman I ever saw breastfeeding. The year was 1972, and I was a college freshman. I’d gone home for a break, and went to see the family of a two-and-a-half year old boy I had babysat for during high school. Timmy was a high spirited, very bright child, and he and I got along well. His parents told me I was the only babysitter to ever come back a second time! That fall of 1972, Timmy’s mom had a second baby, and named that little girl Melissa, in honor of me. And little Melissa was the first baby I ever saw breastfeeding! Her mom made it seem so normal, and so loving, and so right.

It would be years before I became a mother, and I knew from the start that I’d breastfeed my babies.

For some women, the first baby they saw breastfeeding happened in their childhood. Johanna tells of her early memory:

When I was four years old I saw my aunt breastfeeding my cousin. I was dumbfounded. I’d never heard of such a thing. My baby sister was the same age and was bottle-fed. I was fascinated and I know I stared. No one seemed embarrassed. My mother explained that breasts make milk and some mothers choose to feed their babies that way. Later, I babysat for a neighbor with five children, all breastfed. She didn’t make a big deal of it and acted as if were perfectly normal, which it is.

I guess I always knew I wanted to breastfeed.

Connie has similar early memories of babycare:

As a five-year-old, I recall watching my mother rocking my baby brother but for some reason I can’t recall her breastfeeding. Ten years later my sister was bottlefed, so when I was 13 or 14 and I saw a cousin breastfeeding her newborn in a quiet corner of our living room surrounded by her mother and three aunts. I can recall that quite well. Her aunts were touting all the advantages of breastfeeding, one of which I was interested in the most: natural child spacing. That would have been around 1961.

Much like a newly hatched duckling will imprint on the first thing it sees as “mother,” these early memories happen long before a woman is actually holding her baby to the breast the first time, but they leave an indelible impression, and perhaps that’s all part of synching the outside world with our own biology. Maybe we remember those times because we need to remember those times so we’ll have them in our shared memory bank for when we are ready for them.

Role models for breastfeeding are not just the first person we remember seeing breastfed. Those images only lay a foundation for what is needed later on. Regardless of whether we live in a culture in which breastfeeding is the accepted norm, or one in which it is not so publicly integrated, being surrounded by others who are breastfeeding when we get ready to do it ourselves helps us learn tips and techniques for both the easy times, and the challenges. We learn confidence by watching another woman breastfeeding, and we also learn that even when there are challenges, we can find ways to work through them. And we, too, become role models for future breastfeeders.

This is the very foundation of organizations like La Leche League International—built on the notion of shared experience, and learning from our peers. It started simply enough, with a group of seven mothers who realized that the power they felt nursing and sharing among themselves could be shared more broadly through ongoing meetings. These meetings filled the need to be surrounded by “kindred spirits,” especially in areas of the world where those breastfeeding role models were fewer and further between.

Marian Tompson’s memoir, Passionate Journey—My Unexpected Life, tells her story of her own life experiences that ultimately led to connecting with the other six founders of La Leche League to share their passion for parenting their babies through breastfeeding. She sets the stage for how her early life and choices in the 1950s in the Chicago, Illinois, USA, area helped her see the need—and have the confidence to respond to that need—for more role models for breastfeeding.

We’re including a chapter from Marian’s book, “Doing the Right Thing After All,” in which she describes motherhood in the U.S. in the 1950s, and how she built her own confidence through both experience and validation by others. Marian and the organization she helped to found have become role models for thousands of women around the world—many of whom, in turn, have carried that tradition forward and are the role models today.

As you read the chapter and the other articles in this month’s issue of this newsletter, dedicated to role models for breastfeeding, think about who your role models have been.

Doing the Right Thing After All

Chapter 7, Marian Tompson’s memoir Passionate Journey— My Unexpected Life

During the past 50 years, I can’t tell you how often a mother or father has come up to me at an LLL gathering and admitted that as a result of being in La Leche League, they were parenting their children so differently than they had originally expected to and so differently from the way they had been brought up. “I’ll kill myself if they don’t turn out” was a common refrain.

We all want to do the best for our children. So what led me to make the kind of choices I did? First of all, I was influenced by the way I was raised and by the aunts and uncles who surrounded me. Then there were books that impressed me: Childbirth Without Fear and Cheaper by the Dozen. Though I didn’t realize it at the time, I think being fully “present” during a planned, unmedicated birth also had an influence. Birth is a holy moment, and I’ve even seen a father drastically change his expectation of the kind of parenting his newborn needed, just because he was present when his daughter was born. This particular man’s mother had worked throughout his childhood, and he just expected his wife would do the same. But being present at the birth of his first born buried that notion in his mind forever.

A commitment to breastfeeding has another huge influence. All that skin-to-skin contact and closeness evokes a hormonal response that creates a different kind of bond between a mother and her baby. I remember telling Tom after Melanie was born that even if breastfeeding was no better than formula-feeding, I wanted to breastfeed all my babies because that closeness felt so good. It was the effect of my choices, along with the people those choices brought into my life, that supported and shaped my parenting.

Snuggling baby Brian

With our first three daughters born in less than three years, it seemed like I was always holding a baby or toddler, or both. Tom would leave in the morning while I sat in the rocking chair in the living room nursing the baby, with Melanie and Deborah playing on the floor beside me. As often as not, he would come home at the end of the day and walk in the door to see me rocking the baby, with the toddlers still close at hand. When the baby cried, I would pick her up. Much of my housework didn’t get done because the children came first, and I began to wonder if something was wrong with me. My neighbors, most of whom were bottle-feeding and living by the four-hour feeding schedule, seemed to be so much better organized. Their houses always looked neat and tidy. I secretly suspected it was a weakness in me that led me to carry my baby around because I couldn’t stand to let her cry. It took a while, but I finally came to believe that it was probably the effect of my birth and breastfeeding experiences that helped mold me into the kind of mother my babies needed.

Few women breastfed at that time, and many were not even aware that it was an option. One day at the grocery store, Philip, who was only a few weeks old and lying in the cart, started to cry as one of my neighbors came down the aisle. “Oh, time for a bottle!” she said as she passed by. “Oh, no, he’s never had a bottle,” was my response. My neighbor skidded to a stop, turning her cart around to get back to me again. “You mean he’s drinking from a cup already?” she asked incredulously. That Philip might be breastfed never entered her mind.

Babies were not usually taken out to public gatherings in those days, especially in the evening. It was expected they would be left at home with a baby sitter and a bottle. Many times our baby was the only infant present when we attended talks about the family. The few baby carriers available in those days were usually slings designed to help support an older baby on his mother’s hip. But then I read a magazine article about a couple who wore their baby in a carrier on their back when hiking in the mountains. This was before carriers with metal frames were invented, so a baby had to be at least six months old before it could be used. But it seemed like such a great way to carry the baby, while having your hands free to hold on to other children. I wrote to the magazine, got in touch with the couple in the article, and discovered the Gerry Carrier, and voila! Mary White and I soon sent off for our own. We never did use them in the mountains, as Franklin Park is pretty flat, but they sure made it easier to take baby along, no matter what we were doing.

For the first three months of his life, Phillip needed to be close to me, and stayed cozy in the Mexican rebozo

Around this time, Mary told me about a lecture series on parenting being given by Dr. Herbert Ratner, the Health Commissioner of the city of Oak Park. The first one Tom and I attended covered the “terrible twos” and the “trusting threes.” Typically, the evening started with a film from Canada showing children of that age in real life situations. Then Dr. Ratner opened up the discussion to the parents. Everyone was welcome to ask questions. Dr. Ratner spoke about that particular developmental stage and gave suggestions on how to handle different kinds of situations that might arise. It was a perspective that resonated deeply with my own mothering style. Walking out of the auditorium, it was with a great sense of relief that I turned to Tom and said, “We have been doing the right thing after all!” How liberating it was to have Dr. Ratner’s validation! From then on, I could keep on picking up my babies, enjoy the toddlers, and ignore the dust bunnies under the couch and not feel guilty about it.

Dr. Ratner also said something else that evening that further endeared him to me: “Show me a mother with a perfectly clean house and I’ll show you a woman with serious psychological problems.” Little did we know then that Dr. Ratner was not only to become an important person in our family’s life, but that his philosophy would later permeate the lives of thousands, probably millions, of families through La Leche League.

I once again began to find myself out of step with the modern woman when Betty Friedan’s book, The Feminine Mystique, came out. In 1964 she was the keynote speaker at a meeting of the Maternal and Child Health Association in Springfield, Illinois. Dr. Ratner drove several of us to the meeting. This included three-and-a-half month old Philip and Melanie who would celebrate her 14th birthday that weekend. During the keynote, Philip wanted to nurse, so I opted to go into the bathroom and stood there nursing him when a young nurse burst through the door. “Isn’t it wonderful what Betty Freidan says,” she exclaimed, “how we can measure our worth, just by getting a job!” But then she paused, noticing Philip nursing, and said, “But I’m so glad my mother didn’t feel that way.”

Why was I in the bathroom nursing? Well, I had been sitting at a round table with six or seven doctors and was quite certain they would be very uncomfortable if I started nursing Philip in front of them. That would make me uncomfortable, too, and I just didn’t want to have to deal with it.

The next day at a breakout session, Betty Friedan went into more detail about why it was important for a woman to have a paycheck as a confirmation of her worth. So I stood up, Philip in my arms, and explained that just seeing Philip breastfeeding, happy, and healthy, and knowing how I contributed to this was all the justification I needed to feel important as a woman. With that, Ms. Friedan walked over to me, drew herself up, and said, “You are building up your self esteem at the expense of your baby!” Imagine! I realized then that we were the product of two very different life experiences, and she might never understand why I enjoyed and valued being a mother.

A walk in the park with my parents and children

So by 1956, I was the happy, though often tired, mother of four beautiful daughters under the age of seven, I was married to an incredibly supportive husband, and I’d met five people who would become key players in the rest of my life: Doctors Ratner and White, Mary White, Edwina Froehlich, and Betty Wagner, who, along with three other women I was soon to meet, would become the cornerstone of an effort that would ultimately affect mothers and babies around the world.

Following My Instincts

Nanda Gasparini Sharples

I do not think there was one person in particular who was my role model for my experience breastfeeding my daughter, but without a doubt there have been many women who served as models: Close friends who had children before I did and breastfed openly, wherever and whenever. The breastfeeding counselor at the breastfeeding support group here in Cambodia where I live, talked so naturally and calmly about the subject. She supported me during the only challenging moment when my daughter, then 4 months old, was going through a few days of having a hard time latching on. The counselor helped me so much the day I saw her and with the messages that she sent me, that three years later my daughter was still breastfeeding! But most of all, my role models have been the wonderful women with whom I have worked in various parts of the world, in Venezuela, Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands, Vietnam, Laos… women, mostly indigenous, who breastfeed because that is what we humans have been doing for millions of years. They have been a reminder of what is basic for our race.

At first when I was pregnant, I was sure I would follow the common western model— breastfeed on a schedule, only for six months or one year, and then give the bottle. Nothing different crossed my mind because that is what I grew up with. But once my daughter was born, everything changed. I let myself follow my instincts; at times remembering the women I had met working, and my friends. I also think that being an expat in Cambodia, and being married to an Australian, was fortunate because I was far from my culture and the pre-established norms. Being a guest in this country, I felt I was free to follow my instinct and that of my daughter, and not the model of others. And that is how it was. My daughter has been an expert breastfeeding and she nursed when she wanted and where she wanted, for as long as she wanted. We still joke with my husband, my daughter and I that I breastfed at home, on the motorbike, in the car, on boats, in forests. and even under a tree sitting at the edge of a national highway. It has been a wonderful experience, both for my daughter and for me. We have shared so many beautiful moments, it has connected us so much. It has kept her so healthy emotionally and physically. And it has given me so much peace and so many moments of tranquility.

A Friend Saved the Day

Noelia Barros

The 15th of September, 2015, was the start of our journey with breastfeeding. At first it was not easy— we had to overcome cracked nipples, engorgement, and, due to an incorrect diagnosis, mastitis, followed by an intervention that left a wound that would not heal. But I kept my commitment knowing that when you want something you can do it! I attended various breastfeeding counseling sessions, but it wasn’t until I talked to a friend who gave me all the tools to finally succeed with a good latch and everything flowed after that. I clearly remember that day because finally it stopped hurting!

Two years later, I got pregnant again. I never stopped breastfeeding— I continued while I was pregnant as it was the healthiest thing I could do. My daughter is one of those children who do not wean despite a decrease in supply during the second trimester, the change in taste, the first days of colostrum, or even a separation of five days due to complications from a cesarean. When I returned home, we started tandem nursing. Again I came across several difficulties… the main one was the strong feelings of rejection while nursing (that unpleasant feeling of not wanting to nurse my eldest daughter). However, we are surpassing it one day at a time. Despite not having much information and that generally people do not look kindly on breastfeeding in tandem, I am fortunate that I am surrounded by unconditional support. We are at two months and a few days into this adventure that started two years and eight months ago and the breast is comfort, nourishment, love, safety, tranquility. Love multiplies, nourishment is sufficient for two, and going topless takes on a completely different meaning. The hugs between siblings and the bond we are creating make all those sleepless nights, the exhaustion, and the dark circles under my eyes worth the joy of seeing this love that grows!

Noelia Barros, originally from Argentina, lives in Paraguay with her partner, Gustavo. She is the mother of Adriana, 2 years old, and Federico, 2 months and 10 days at the time of writing her story. Together with Gustavo, they decided that the best thing would be for her to stay home and take care of the children and so has been doing this since Adriana was born. In her own words “I am not a perfect Mom—in fact there is no such thing—I just try to do what I think is best for my children”. She is passionate about learning new things and recently discovered she has a talent for quilling paper, and so she has now started a business making pictures using this technique.

At First, I also Struggled to Nurse my Baby

Hanny Ghazi (translated from French by Suzi Livingstone)

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends exclusive breastfeeding until 6 months of age, after which babies should be given complementary foods and continue breastfeeding up to the age of 2 years or beyond (1). However, in France, our statistics fall short of these goals, largely due to the fact that our maternity leave is shorter than the 6 months in which we are recommended to exclusively breastfeed. The majority of mothers who breastfeed in France do so until the end of their leave, around the third month of their babies’ lives. (The legal duration of maternity leave varies according to the number of children, with a leave of 16 weeks for a mother of one.) (2)

I am an Anthropologist, with a Masters in Middle Eastern History, but the arrival of my first child 5 years ago caused a 180° shift. These days I am interested in all matters related to the perinatal period. I have become a Doula (birth partner), and I am also a breastfeeding counselor.

Breastfeeding my first child was a challenge, and it’s due to the fact that I was able to overcome the obstacles and breastfeed successfully that I became passionate about the subject.

Last year I gave birth to my second child and I was confident that this time I could take care of breastfeeding my baby by myself. But once again I encountered challenges, so here I am today with yet another experience to share.

With my daughter’s birth, I had a week of early labor where she wouldn’t engage in my cervix in order to descend and emerge. This situation may have been due to cervical dystocia 【1】, and considering my exhaustion (and worried that my baby may also be worn out), the obstetrician suggested a cesarean. My daughter was born and the first “feed” took place in the recovery room. I put “feed” in quotations because my baby was drowsy due to the anesthesia, which is normal (3). After a cesarean birth, it is especially important to hold the baby skin-to-skin (4) as much as possible, as this physical contact stimulates the release of oxytocin, an essential hormone in milk production.

The first night of my baby’s life was peaceful, with her lying on me (5), me being careful not to let her touch my scar, and letting her rest quietly and then putting her to the breast as soon as she woke. The next day, however, I was informed she was at risk for jaundice, which was confirmed by transcutaneous bilirubin measurement, meaning that she wasn’t receiving enough milk, despite a good latch and regular nursing. I looked inside my baby’s mouth and noticed both a tongue and a lip tie (6) that would eventually need to be released in order to get a better latch. I had packed a small spoon in my hospital suitcase to supplement my baby’s feeds with hand-expressed colostrum, should we encounter difficulty nursing. The next morning her bilirubin had decreased and I was granted an early discharge from the maternity ward.

The first night of my baby’s life was peaceful, with her lying on me (5), me being careful not to let her touch my scar, and letting her rest quietly and then putting her to the breast as soon as she woke. The next day, however, I was informed she was at risk for jaundice, which was confirmed by transcutaneous bilirubin measurement, meaning that she wasn’t receiving enough milk, despite a good latch and regular nursing. I looked inside my baby’s mouth and noticed both a tongue and a lip tie (6) that would eventually need to be released in order to get a better latch. I had packed a small spoon in my hospital suitcase to supplement my baby’s feeds with hand-expressed colostrum, should we encounter difficulty nursing. The next morning her bilirubin had decreased and I was granted an early discharge from the maternity ward.

In order to relieve any cervical spine tension that may also have been affecting my baby’s latch, I took her to see a pediatric chiropractor in Paris, and we then saw a pediatric odontology specialist in order to get her opinion on my daughter’s lip and tongue ties. The specialist agreed to the need for a double frenotomy, a procedure that lasts only 10 minutes and after which the latch improved dramatically.

One week had passed, my little one was gaining weight appropriately, her skin was soft and smooth, she slept several hours a day, nursed at least 10 to 12 times in 24 hours, and produced enough wet diapers (7).

Everything was going well, except… My breasts seemed to be producing much more milk than my daughter needed. They never seemed to empty, even after “good” (long) feeds. When my daughter was at the breast the other one leaked non-stop, and I found myself soaked unless I covered myself with a clean blanket (which was also soaked at the end of the feed), and I needed to change my shirt several times a day. The weekend before my husband’s return to work (no doubt due to my anxiety over his imminent absence), I experienced engorgement that ended in mastitis (8).

Normally, the first weeks after birth are key for establishing breastfeeding. Your body “reads” the frequent feeds and is able to determine how much milk it needs to make in order to satisfy the baby’s demands. My daughter was already a month old but it seemed my body still had not determined the quantity of milk necessary to feed her.

The most common reason that women stop breastfeeding is a “lack of milk,” a condition that in reality occurs in very few women, who have a physiological pathology preventing them from producing the amount of milk their child needs (9). Partial breastfeeding is always feasible in these cases, and sometimes it is even possible to work up to exclusive breastfeeding with the support of a specialist.

The most common reason that women stop breastfeeding is a “lack of milk,” a condition that in reality occurs in very few women, who have a physiological pathology preventing them from producing the amount of milk their child needs (9). Partial breastfeeding is always feasible in these cases, and sometimes it is even possible to work up to exclusive breastfeeding with the support of a specialist.

Excessive milk production is a pathology as well, less frequent and less studied, which can also lead to women stopping breastfeeding. Overly full breasts are hard for a child to latch onto, and the oversupply can lead to a strong letdown (and it’s unpleasant to drink milk from a garden hose!). Oversupply can also lead to colic and discomfort since the force of the milk stream causes the child to swallow air while nursing, babies’ bowel movements may be green and explosive, and they can have stomach aches from drinking too much lactose (which is more present in foremilk).

In order to get out of this situation that was leaving both my daughter and me miserable, I started by nursing in a position that allowed my baby to let milk spill out of her mouth if it came out too quickly (lying down), I offered her the breast regularly so she wouldn’t be too hungry (and therefore nurse too vigorously), and I also tried block feeding, 【2】since not fully emptying the breast gave my brain the message to slow down production. When I woke up in the morning with full breasts I tried to completely empty them with the help of an electric pump. Herbal teas with strawberry, mint, and clary sage gave my body the final push to regulate production (10).

Breastfeeding is an art, a learned art that was once passed down from mother to daughter, in tribes, in community. Today we live far from our parents, locked in our apartments and lacking community. For young mothers, participating in support groups (11) allows them to share experiences and tricks necessary to learning and perfecting this art, and in exceptional cases, additional support from a professional may be necessary.

Hanny Ghazi originally came from Colombia, and now lives in France with her French husband and their son, Emilio, 6, and their daughter Agnès-Rose, 10 months. She has been a La Leche League Leader since December 2014. Hanny created an LLL support Group for Spanish speaking mothers in the Paris area in May 2015.

【1】Difficult labor and delivery caused by mechanical obstruction at the cervix.

【2】 Block feeding means keeping the baby to one breast for blocks of time (usually for 3 hours or longer) before switching to the other breast. Click here to learn more about this technique.

References

[1] http://www.who.int/nutrition/topics/exclusive_breastfeeding/fr/

[2] https://www.lllfrance.org/vous-informer/actualites/1825-les-derniers-chiffres-de-l-allaitement-en-france

[3] https://www.has-sante.fr/portail/upload/docs/application/pdf/2013-07/brochure_patient_cesarienne_mel_2013-07-02_11-25-35_632.pdf

[4] Colson S. (2006). The mechanisms of biological nurturing (Doctoral thesis, Canterbury Christ Church University, Canterbury, England). Available in PDF format from The British Library: Thesis Collection.

[5] http://biologicalnurturing.com/assets/fr/maternage%20corporel%20poster.pdf

[6] http://www.reseau-naissance.fr/data/mediashare/hs/ecj4b1rwo2hv9glypv2lpazk4fwda1-org.pdf

[7] https://www.lllfrance.org/996-mon-bebe-prend-il-assez-de-lait

[8] https://www.lllfrance.org/1486-mastite-aigue-ou-lymphangite-mastites-chroniques-et-recidivantes-abces-du-sein

[9] https://www.lllfrance.org/1107-manque-de-lait-mythe-ou-realite

[10] https://www.lllfrance.org/vous-informer/fonds-documentaire/dossiers-de-l-allaitement/1344-da-77-traitement-production-lactee-surabondant

[11] https://www.lllfrance.org/vous-informer/fonds-documentaire/allaiter-aujourd-hui-extraits/1124-41-soutenir-les-meres-qui-allaitent-le-role-des-groupes-de-meres

Breastfeeding is Beautiful at its Core

Ivana Cortez

My name is Ivana, and on October 23, 2017, I became the mother of Ignacio. During my pregnancy I made sure to be informed about breastfeeding and I knew and I was sure that I wanted “to give the breast.” During the last few pregnancy check-ups I told my obstetrician to please not give formula to my baby after birth. During the cesarean, I repeated it—please do not give formula and even dad was very clear on this too. When I was taken to the room, I found my beloved son with an immense desire for the breast and from that moment began our adventure.

My name is Ivana, and on October 23, 2017, I became the mother of Ignacio. During my pregnancy I made sure to be informed about breastfeeding and I knew and I was sure that I wanted “to give the breast.” During the last few pregnancy check-ups I told my obstetrician to please not give formula to my baby after birth. During the cesarean, I repeated it—please do not give formula and even dad was very clear on this too. When I was taken to the room, I found my beloved son with an immense desire for the breast and from that moment began our adventure.

I continued to inform myself on breastfeeding—how to overcome pitfalls along the way, that breastfeeding does not hurt, that contrary to what I was told at the clinic it is best to not keep track of the clock, and that is how I did it.

Despite my knowledge, I still had challenges to overcome. Ignacio was putting on weight fantastically, but the pediatrician would still say “try formula because we need Plan B for when you go back to work.” At the next check-up she would insist “you have to try formula,” or the comment “give him a bottle so he sleeps through the night.” I never paid any attention; I followed my instinct and the needs of my baby. We also kept going despite comments like “it is habit, not hunger,” “that baby is at the breast all day,” “how often does he eat? You feed him all the time!” and I could go on! And this is where the beautiful part comes in— my role model. Thanks to social media I got to know La Leche League and I was able to attend their monthly support group meetings where I felt supported, understood, and encouraged to continue with breastfeeding. And thanks to La Leche League I got to know my role model for breastfeeding— Alejandra Galvan. Without knowing me and with total predisposition, she listened to me from the very beginning and clarified all my doubts. Thanks to her I was able to stock up on breastmilk before going back to work. She may not know it, but she is the person who has been and is the key reason for Ignacio having a happy breastfeeding journey!

Despite my knowledge, I still had challenges to overcome. Ignacio was putting on weight fantastically, but the pediatrician would still say “try formula because we need Plan B for when you go back to work.” At the next check-up she would insist “you have to try formula,” or the comment “give him a bottle so he sleeps through the night.” I never paid any attention; I followed my instinct and the needs of my baby. We also kept going despite comments like “it is habit, not hunger,” “that baby is at the breast all day,” “how often does he eat? You feed him all the time!” and I could go on! And this is where the beautiful part comes in— my role model. Thanks to social media I got to know La Leche League and I was able to attend their monthly support group meetings where I felt supported, understood, and encouraged to continue with breastfeeding. And thanks to La Leche League I got to know my role model for breastfeeding— Alejandra Galvan. Without knowing me and with total predisposition, she listened to me from the very beginning and clarified all my doubts. Thanks to her I was able to stock up on breastmilk before going back to work. She may not know it, but she is the person who has been and is the key reason for Ignacio having a happy breastfeeding journey!

Breastfeeding does present a lot of challenges along the way, in particular from our society, and it can also be exhausting, but it is beautiful at its core. An experience, with my son, that I would not change for anything!! I hope there will be more and more babies and mothers with happy breastfeeding stories. Thank you for giving me the opportunity to share!

Breastfeeding does present a lot of challenges along the way, in particular from our society, and it can also be exhausting, but it is beautiful at its core. An experience, with my son, that I would not change for anything!! I hope there will be more and more babies and mothers with happy breastfeeding stories. Thank you for giving me the opportunity to share!

Ivana Cortez lives in Cordoba, Argentina. She lives with her partner and son, Ignacio. She is an educational psychologist and works with children who have learning difficulties. She is with them in the classroom and is their bridge to learning—helping to adapt the teaching process so they can understand what is being taught. She loves her job and seeing them learn is something that fills her soul. Becoming a mother has made everything take on a different meaning, and since Ignacio’s birth she has fallen in love with her capacity to feed him from her body, and everything else this allows—being together! While he wants, they will continue with breastfeeding!

Establishing a Model Campus-Wide Breastfeeding Program in Connecticut

Michele Vancour, PhD, MPH and Chandra Kelsey, MPH

Southern Connecticut State University’s commitment to a social justice mission, and the values of dignity, respect, kindness, compassion, and civility are just a few reasons why our campus was ready to take a big step forward in supporting breastfeeding. As a university that is invested in sustaining a culture of care, there was excitement to create equal access to lactation supports on campus so parents are able to achieve their breastfeeding and academic/career goals.

Southern Connecticut State University’s commitment to a social justice mission, and the values of dignity, respect, kindness, compassion, and civility are just a few reasons why our campus was ready to take a big step forward in supporting breastfeeding. As a university that is invested in sustaining a culture of care, there was excitement to create equal access to lactation supports on campus so parents are able to achieve their breastfeeding and academic/career goals.

While Connecticut breastfeeding laws protect employees’ rights to breastfeed or pump at work, there currently are no laws to protect students’ or visitors’ rights on campus. As a result of the recent changing student demographics (more non-traditional students with/starting families), we recognized the need to reimagine our approach expanding it beyond the existing work law. Promising practices found among from other universities’ lactation programs, Ontario’s Breastfeeding-Friendly Campus Initiative, and Breastfeeding Best Practices in Higher Education (Vancour & Griswold, 2014), led to plans for Southern’s enhanced breastfeeding support initiative. Our lessons learned demonstrated the need for a culture change at Southern in order to engage the entire campus community, increase visibility, promote lactation support and resources, and maintain efforts over time.

We were quick to realize that a shared responsibility approach was the solution to our immediate and future lactation needs. We observed that while many campus lactation programs prided themselves on the quantity of permanent lactation spaces, they continuously were trying to identify more spaces. Given that little progress had been made since Southern’s first lactation room was established in 2006, we were confident that we could accomplish more in less time with a committed group dispersed across campus than was previously possible with only a few people.

With limited financial resources, promising practices in hand, a strong connection with the Connecticut Breastfeeding Coalition, and a big leap of faith, the initiative began with a pilot in our School of Health and Human Services. Two weeks from the announcement that the School was working towards becoming breastfeeding-friendly, six out of eight departments reported at least one assigned person, a Breastfeeding Champion, who would serve as their main point of contact. The response was overwhelmingly positive and within a few months, the entire campus was eager to join the effort.

Currently, Southern has 56 Breastfeeding Champions (students, faculty and staff), representing 40 departments on campus. The number of Champions and their enthusiastic responses top the list of our most impressive accomplishments related to our Breastfeeding-Friendly Campus Initiative. This is followed closely by the identification of new temporary and/or permanent lactation spaces across campus. In addition to a centrally located multi-user space in our library, we have six temporary spaces and one permanent space. Consistent with best practices, lactation rooms are planned in all future new buildings on campus. Our Champions continue to search for creative space solutions that are easily accessible and available when needed. We are confident that the number of identified spaces will increase over the next academic year.

A celebratory group of Southern’s Breastfeeding Champions

Another important accomplishment was the heightened awareness of breastfeeding on campus. Several departments and Breastfeeding Champions worked together to create posters, privacy door signs, stickers, electronic bulletin board messages, and t-shirts to promote the message, “Southern Supports Breastfeeding on Campus.” Additionally, messages were placed on Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook, in addition to press releases and articles that were shared through campus publications, social media, and local press.

Last, but most instrumental, is our community partnership with and recognition by the Connecticut Breastfeeding Coalition. We are the first campus in the state to receive the Coalition’s new Breastfeeding-Friendly Campus Award. A celebration and award ceremony was held with Southern’s Breastfeeding Champions in March 2018. Since news of this designation received attention from local and national press, we have heard from other institutions looking for guidance in starting initiatives on their campuses, and we are proud to be a leader in breastfeeding on campus.

Michele Vancour, President Joe Bertolino, and Chandra Kelsey

Reflecting on our journey, we recall some important lessons learned. Undoubtedly, approaching our initiative from a shared responsibility perspective was a game changer. Having this collaborative method created buy-in and provided a group of caring and committed community members with whom we can share the success. As a result, we are receiving notes of appreciation from people on campus who are experiencing the shift in practice. They let us know that they are thankful that there are convenient places for them to pump, colleagues to support them, and that they feel empowered to be part of the culture change. We expect this initiative to make a positive impact on our recruitment and retention rates as well as academic success and job satisfaction. Knowing you are making such a big difference for families is worth it.

For more information on Connecticut’s Breastfeeding-Friendly Campus Initiative, please contact: Michele Vancour at vancourm1@southernct.edu or Chandra Kelsey at info@breastfeedingct.org.

How a Breastfeeding Initiative in Rural Kenya Changed Attitudes

Judith Kimiywe and Elizabeth Kimani-Murage

Photo Credit: Alissa Everett/Reuters

There’s a growing global recognition of proper infant nutrition in the child’s first 1000 days of life. This can be monitored through encouraging proper nutrition during pregnancy and the first two years of life for optimal growth, health and survival.

Poor breastfeeding and complementary feeding practices are some of the common causes of malnutrition in the first two years of life. Breastfeeding confers both short-term and long-term benefits to the child like reducing the risk of infections and diseases like asthma, obesity, and type 2 diabetes. Mothers who breastfeed also lower their risk of developing breast and ovarian cancer, weak bones, obesity and heart disease.

For countries to reap the benefits of breastfeeding they need to achieve a baby friendly status. Kenya began promoting the baby friendly hospital initiative approach in 2002. It ensures that health facilities where mothers give birth encourage immediate initiation of breastfeeding and exclusive breastfeeding for the fist six months. Unfortunately, this program was only accessible to women who delivered in the health facilities, leaving out those who gave birth at home.

We conducted a two year study involving 800 pregnant women and their respective children in a rural area in Kenya.

My experience of supporting my wife to breastfeed our first child

By Jean-Marie Nkurunziza

It was a very hard period for my wife and me after we had our first child. She had delivered by C-section, and therefore it was not easy for her to take care of the baby, breastfeed, or do other work at home like cooking.

Jean Marie Nkurunziza with his wife Gugulethu Nkurunziza and daughter Latoya. Photo Credit: Elisabeth Ubbe.

Becoming a parent was a very joyful moment for both of us. When I was younger, I couldn’t believe that one day I would become a father. Although it is a joyful experience, it is not an easy responsibility for mothers, since women often have a lot of tasks to do after the baby is born. During the time when my wife was breastfeeding, I could see that it was also not easy for her due to her recovery from the C-section. It took a lot of effort from us to care for the newborn; this care work would easily fill up a full 24 hours. My wife needed my daily practical, moral, and psychological support.

While it was also joyful for me, everything was new. I did not know what to do when the baby was crying, or whether she was hungry or sick. At the same time, my wife was still in recovery, and our child arrived in June, when it is very cold in South Africa.

I was grateful to my organization Sonke Gender Justice for providing us with paid parental leave of four weeks for fathers. This allowed me to be at home with my wife and child to provide care and support to my family. It was special to be sharing responsibility with my wife. She breastfed the baby, and I did the household work like cooking, washing dishes and clothes, and caring for our plans. It became my responsibility to do everything that was needed around the house.

Our baby often cried in the middle of the night. This made my wife uncomfortable, as she had to wake up and breastfeed her. I would support my wife by picking up our daughter to calm and console her, checking or changing her diaper, and putting her back to sleep. I would also feed her expressed milk while her mother was sleeping.

The breastfeeding period may often be hard for mothers, and it is during this time when mothers most need the support from their partners.

About Jean-Marie Nkurunziza:

Jean-Marie Nkurunziza is a Burundian who started working for Sonke Gender Justice as a volunteer. He is now a Children’s Rights and Positive Parenting Regional Trainer, working with parents and young men on issues related to fatherhood, gender equality, and caregiving. Jean-Marie is committed to promoting gender equality; stopping gender-based violence; spreading HIV/AIDS awareness; and improving men’s participation in care work, caregiving, and gender equality in his community and around the world.

About Sonke Gender Justice:

Sonke Gender Justice is a non-partisan, non-profit organization established in South Africa in 2006. Today, Sonke has established a growing presence on the African continent and plays an active role internationally. Sonke works to create the change necessary for men, women, young people, and children to enjoy equitable, healthy, and happy relationships that contribute to the development of just and democratic societies. Sonke pursues this goal across Southern Africa by using a human rights framework to build the capacity of government, civil society organizations, and citizens to achieve gender equality, prevent gender-based violence, and reduce the spread of HIV and the impact of AIDS.

How I’m Right and My Wife Isn’t

Arthur Molloy

Photo Credit: iStockphoto.com/ jacoblund

A father’s story

While we generally agree on the way we parent our children, it must be said that the initiative comes mainly from my wife; she looks to the long term.

A rare story: how I’m right and my wife isn’t

And so this story is particularly exceptional in that it is the story of how I’m right and my wife isn’t.

I’m often accused of passing the baby back too quickly.

Let me explain. We have a baby, our third, who is two months old now and, after enjoying two spirited boys, we are now relishing the challenge of having a little pink in our lives.

In the course of the days she is passed to me, but as soon as she so much as wriggles I hand her back to her mother for breastfeeding.

“She mightn’t want feeding,” says my wife, “maybe she’s wet, tired, bored, over-stimulated. You don’t have to always assume she needs feeding.”

So maybe now you’re thinking, “What a selfish man! Does he ever give his wife a break?”

Yes I cuddle our daughter, I lie with her at night, I cradle her in a sling and I pull silly faces while her mother tries to gulp down a cup of tea, and yes, as soon as she squirms in my arms, I hand her back suggesting she might need feeding. And sometimes that’s five minutes after she last fed, sometimes it’s thirty minutes.

But wait for it—here comes the bit where I’m right: maybe it’s not hunger causing her to wriggle about, but breastfeeding is pretty much always always the answer. Tired baby? Breastfeed her. Bored or over-stimulated baby? Breastfeed her. Baby too hot or too cold? Snuggle her close and breastfeed her.

So much more than a feeding system, breastfeeding is nature’s perfect answer to all of a baby’s ailments.

Handing the baby over to mum is definitely an act of love for me. For our family, the very best place for our baby is in her mother’s arms.

My arms will always be there, waiting for her. I will hold her hand as she takes her first steps, as we chase the waves on the beach, as I walk her down the aisle and she nurses children of her own. My arms will forever form a protective barrier for her.

And so for now my arms will pass her to her mother. And, okay, maybe breastfeeding won’t cure a dirty diaper, but I’m happy to pass that one over as well—I can’t be right all the time!

This article was first published in Breastfeeding Today on June 1, 2013. We would like to thank the author and La Leche League international (www.llli.org) for granting us permission to share it.

How Working Mothers Can Be Role Models for Breastfeeding

Vania Smith-Oka

Years ago, when I was nursing my own daughter (now eight years old) I read a wonderful online article by Kristin Berggren (who writes about breastfeeding for working moms) about how breastfeeding is like riding a bike—even if we’ve never ridden a bicycle we know what it consists of as we’ve seen others ride. Conversely, Berggren said, because breastfeeding is so often hidden—under blankets or behind bathroom doors—people don’t really know what it actually entails until they have children of their own and then frequently don’t know what to do because they’ve had no female role models to look up to and help them to do this. In some contexts breastfeeding is obviously very commonplace and public breastfeeding normalized, where children are exposed to it early on, while in others there are more norms about nursing practices and so there are fewer chances of seeing it “in action.”

Photo Credit: iStockphoto.com/ Sasiistock

What would happen if breastfeeding were normalized everywhere? And what if this normalization extended to seeing moms breastfeeding their children at work—whether at their desk, in a meeting, or on a congress floor? Motherhood and breastfeeding rarely overlap in the workforce. Many mothers work, and some even manage to breastfeed for extended periods. But in these workspaces their identity is that of worker—lawyer, professor, doctor, teacher, chef, etc. They have to separate their two identities in time and place—at home they are moms, and at work they are workers. Rarely do these two identities align.

Fortunately, in recent years more professional women in the public eye are embracing their motherhood: they not only bring their children to work, they often breastfeed them there. Many of us have seen the images and videos of Licia Ronzulli taking her daughter to the European Parliament meetings since she was a baby, or Australian Senator Larissa Waters, Iceland lawmaker Unnur Bra Konradsdottir, or Argentine congresswoman Victoria Donda Perez breastfeeding their children in parliament. Like US politician Kathy Tran said about her decision to breastfeed her child on the delegate floor, “I had a baby that was hungry and I needed to feed her.” These female leaders have been seen as role models for being able to gradually shift these male work spaces into ones that are more accepting of the complex ways that working mothers navigate their dual identities. In turn they have made these spaces more welcoming to women—whether moms or not.

Even more recently, other working mothers are purposefully embracing their dual identities in public forums. Such is the case of Krish Vignarajah and Kelda Roys, both of whom are candidates for gubernatorial seats in the United States. Rather than hiding their realities as young, professional women who also happen to be mothers, they place their motherhood front and center in their campaign ads. In these videos they each breastfeed their infant while discussing the political issues that concern them (also notably visible are their male partners holding, changing, or interacting with the baby). Indeed, their ads suggest, being mothers makes them better leaders, more empathetic, and more able to get things done. Their choice to breastfeed on camera as part of their campaign is an overt way of displaying their motherhood and showing the world that the policies they support are also part of their embodied experience as mothers.

What effect does seeing these professional women breastfeeding have on other women and on society? Well, at first there is likely to be pushback; after all, it’s hard enough for some societies to accept breastfeeding in and of itself, never mind it occurring in public and in “work-only” spaces. Over time, however, if these women persist in breastfeeding publicly we can expect that these role models will shape the behaviors of current mothers as well as influence young girls (and boys) to see breastfeeding as part of women’s rights in all spaces, and to see partners (male or female) as an integral part of childcare. Role models can influence individual or group behaviors as they are people whom others look up to and want to emulate.

But the broader sea change about women’s rights and the freedom to breastfeed cannot come solely through female role models. If we want women to have the same choices as men we need to have structural changes that incorporate breastfeeding into a life and work model. We also need male allies who support these changes, making them mainstream. Obviously not all work environments can incorporate this model—it would be dangerous to hold and nurse a baby on a factory floor or as a server in a restaurant, for example. But some flexibility can, hopefully, allow for women to maintain their income while also breastfeeding their children. What are needed are not only pumping rooms, but also things like on-site childcare, flexible work hours, and nursing rooms where women can breastfeed their children. These changes cannot just be exceptions, like for Tammy Duckworth of the US Senate to bring her baby to work, but rather need to be permanent structural changes that can help other women (and men) navigate work and parenthood.

Ultimately, what we can hope for is a cascade of effects—female leaders breastfeeding their babies at work, sparking other women to emulate them, who then advocate with their allies for structural changes, which increase the opportunities for other women to join the workforce and also be able to breastfeed their children. My own wish is that we’re on the cusp of societal transformation about breastfeeding as a part of working women’s identity.

Vania Smith-Oka is an anthropology professor and mother who breastfed her now-eight-year old daughter for four years. She is firmly committed to supporting working mothers who want to breastfeed and to finding structural solutions to achieve this.

The Dirty Truth about the Infant Formula Industry

Save the Children

How come poor mothers in low-income countries chose industrially processed powder to feed their babies, when most of them have access to a clean, healthy alternative – for free? The Norwegian doctor Line Jansrud, mum and pregnant, is determined to find out more about the infant formula industry, and takes us on a journey from Norway to Cambodia, and back to Norway – where she discovers the disturbing truth about the Norwegian Pension Fund.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HD1t4VBQBBU

Mother Nature Knows Breast

Young Social Innovator award winners from Mount Mercy Girls School, Cork, Ireland

It was October 2015 when Mother Nature Knows Breast first began. As part of our Transition Year programme in our school, Mount Mercy, we entered into the Young Social Innovators competition. This is an Irish competition which centres on getting young people to tackle social issues in new and innovative ways. As a class, we had trawled through newspapers and social media to find different topics to tackle, when the topic of breastfeeding popped up. Admittedly, we weren’t all interested at first, but we chose it anyways, and from there the idea developed into the project it is today.

It was October 2015 when Mother Nature Knows Breast first began. As part of our Transition Year programme in our school, Mount Mercy, we entered into the Young Social Innovators competition. This is an Irish competition which centres on getting young people to tackle social issues in new and innovative ways. As a class, we had trawled through newspapers and social media to find different topics to tackle, when the topic of breastfeeding popped up. Admittedly, we weren’t all interested at first, but we chose it anyways, and from there the idea developed into the project it is today.

As a group of young, 16 year old girls we never realised how impactful breastfeeding could be on a child, and on a population. We decided that a documentary was the best way to create awareness of breastfeeding, and how we have the lowest breastfeeding rate here in Ireland. From there it was nothing but hard work, emails, deadlines and countless hours spent researching things from how health impacts the economy, to post-birth hospital procedures. We applied for grants to fund the project, and elected leaders, such as myself, to run different parts of the project and oversee the progress. I didn’t know then, that I and four other leaders would be still here 3 years later, at the finishing line with our documentary. Later that year, we came second nationally for our work on the project in the Young Social Innovators competition, beating hundreds of projects nationwide. By then we had yet to even begin filming, but with months of hard work behind us, it had all paid off in the form of a silver glass trophy in the prize cabinet of our school.

That summer, our class of 30 had whittled down to five volunteers, who had committed to keeping this project going. I and the rest of my team, Nicole Clarke, Louise Feehely, and Katie Cronin, worked with directors and health professionals to film our documentary.

That summer, our class of 30 had whittled down to five volunteers, who had committed to keeping this project going. I and the rest of my team, Nicole Clarke, Louise Feehely, and Katie Cronin, worked with directors and health professionals to film our documentary.

Now in 2018, we’re finally finished! We have put together a 15 minute documentary, interviewing various health professionals on the benefits of breastfeeding, as well as our situation here in Ireland. It touches on what we need to do as a country to fix our low breastfeeding rate, as well as the facts and figures related to breastfeeding. As a team we also speak on our journey from start to finish in this project, and what it all means to us now.

Our documentary can be found at https://www.facebook.com/mothernatureknowsbreast/, or on YouTube at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0vE1UtNUsSo.

We hope you all enjoy it, and as we say on our team, Boobies for Newbies!

Aisling O’Leary (team leader), Louise Feehely, and Nicole Clarke (social media team), and Katie Cronin (report writing). All four are currently working on their Leaving Cert exams, which are the Irish equivalent of final exams. They are all hoping to go to college next year and are proud that this project is still alive two years on. For further information, please contact Aisling at aislingoleary28@gmail.com.

Normalizing Breastfeeding at an Early Age: Children at Play around the World

“To get back to a status quo in which nursing is once again considered the normal way to feed a baby, children need to grow up seeing it, role-playing it, and not picking up the taboos of the previous generation. Children learn to walk and talk by watching and copying. The more we expose growing humans to their biological norm, the less problems will result when it’s their turn to nurture the next generation.” (Maddie McMahon, a breastfeeding counsellor from the Association of Breastfeeding Mothers)

“ This is Emilia. She is three and a half years old and has been breastfeeding since she was born. Breastfeeding is a part of her life, in her play; it is something natural for her. She organizes La Leche League (LLL) support groups and makes a very unique Leader as she nurses all the babies in the meeting. When she plays with her cousins she teaches them which is the correct way of holding a baby and what to do in case of cracked nipples. The help, love and emotional containment that we have received from LLL has set out our direction in life… we can only give a heartfelt thanks.” Mariana Santoianni, Argentina

This is Emilia. She is three and a half years old and has been breastfeeding since she was born. Breastfeeding is a part of her life, in her play; it is something natural for her. She organizes La Leche League (LLL) support groups and makes a very unique Leader as she nurses all the babies in the meeting. When she plays with her cousins she teaches them which is the correct way of holding a baby and what to do in case of cracked nipples. The help, love and emotional containment that we have received from LLL has set out our direction in life… we can only give a heartfelt thanks.” Mariana Santoianni, Argentina

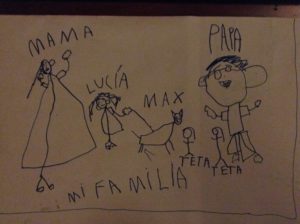

“Since she could talk, Lucia (4 years) would refer to my breasts (“teta” in Spanish) as an individual separate to me. Now she has beautifully illustrated her family on an outing, including each ‘teta’.” Nanda Gasparini, Cambodia

“Since she could talk, Lucia (4 years) would refer to my breasts (“teta” in Spanish) as an individual separate to me. Now she has beautifully illustrated her family on an outing, including each ‘teta’.” Nanda Gasparini, Cambodia

“Amalia enjoys sitting in her room and playing with her various stuffed animals. I went into her room one day to see what she was up to and saw her like this with her favorite dog. She looked up and said “Mummy, I am giving milk to my dog so he feels better.” Natalia Smith, Italy

“Amalia enjoys sitting in her room and playing with her various stuffed animals. I went into her room one day to see what she was up to and saw her like this with her favorite dog. She looked up and said “Mummy, I am giving milk to my dog so he feels better.” Natalia Smith, Italy

“Merrilee nursed Grayson for over three years, and it was an important—and normal—part of his young life. He wanted to share the bounty, and insisted that his mom also nurse Mickey Mouse.” Melissa Vickers, USA

“Merrilee nursed Grayson for over three years, and it was an important—and normal—part of his young life. He wanted to share the bounty, and insisted that his mom also nurse Mickey Mouse.” Melissa Vickers, USA

“Mbendjele BaYaka girls holding their “babies” and miniature breasts they made of cocoa fruits. BaYaka are hunter-gatherers and their culture can show a lot of practices humans did in past. BaYaka practice allomothernal nursing— women breastfeed babies who are not their biological children, and even grandmothers will breastfeed children after menopause. Breastfeeding is a normal activity and people are not “scared of seeing nipples” as it often happens in Western societies. The girls in the picture are not only playing mothers, they are breastfeeding their babies.” Daša Bombjaková, Central Africa.

“Mbendjele BaYaka girls holding their “babies” and miniature breasts they made of cocoa fruits. BaYaka are hunter-gatherers and their culture can show a lot of practices humans did in past. BaYaka practice allomothernal nursing— women breastfeed babies who are not their biological children, and even grandmothers will breastfeed children after menopause. Breastfeeding is a normal activity and people are not “scared of seeing nipples” as it often happens in Western societies. The girls in the picture are not only playing mothers, they are breastfeeding their babies.” Daša Bombjaková, Central Africa.

The Breastfeeding Mother: A Role Model in the Making

As the first stories for this issue of the Newsletter began arriving in our inbox and we put our heads together wondering which Breastfeeding Advocate we would like to honor, it dawned on us that it is the BREASTFEEDING MOTHER who needs an honorary mention. It is that breastfeeding mother who stood by you and shared in those tears when the going was tough, it is that breastfeeding mother who you saw breastfeeding without inhibition at the park, on the plane, or at a restaurant that served as your role model years down the line, it is that breastfeeding mother who sat with you while your learnt the tricks of the trade…. It is all these mothers who by the simple art of breastfeeding are our biggest supporters and advocates. They are an essential role model in this “tapestry of support”. We chose to honor the BREASTFEEDING MOTHER by sharing a selection of photos from the photography project Amamantar from Peru. This exhibit, through captivating images and storytelling, honors the beauty and strength of the BREASTFEEDING MOTHER.

Photography Project Amamantar

Claudia Blanco Pancorbo and Romina Llomovatte Miranda

“Amamantar” (breastfeeding, in Spanish) is the result of an artistic restlessness in search of a social purpose— to show beauty and reality in one same image to create awareness of the importance of breastfeeding. The photographs tell stories and show the different contexts in which Peruvian mothers fulfill the mission to nurture their children emotionally and physically through a practice that, in recent years, has been diminished or threatened by various circumstances.

Through a journey that took us to various sites along the coast, mountains, and jungles of Peru, it was possible to get to know the faces and voices of women who share the same objective of wellbeing for their children, many times hampered by obstacles such as prejudice, social pressure, material deprivation, and the difficulties of bringing up children in remote areas or without basic services. Here we were met with the challenges of being a mother in a community of the north coast, or in the highlands of the Andes, or on the shores of a river in the jungle. This is where breastfeeding comes into play as an effective tool to prevent illnesses and, when possible, secure the optimal growth and development of babies and infants.

Every woman we met on this journey of discovery left us with lessons learned and unfinished work to bring back the value of the experience of motherhood in all its dimensions. We validated that the effort to be the constant giver and provider transcends all cultural, geographical, or economic differences; that this task—never simple—brings together smiles and, at times, physical pain, satisfaction, and emotional exhaustion, with the most important reward— to see their little ones healthy and happy.

The final goal of this exhibit is to revive the commitment of these women to motivate many more, and draw in each visitor to that unique bond that is built when a mother holds her baby in her arms to give her much more than milk.

Socorro Torres Domínguez (37), is mother to María Fernanda, of five months. Due to a severe case of pre-eclampsia she underwent an emergency cesarean when she was 7 months pregnant. The baby was separated from her mother for four days. “When they brought her to me I had no milk and she cried all night because she was hungry and nothing was coming out. The next day I put her back on my breast and, after many tries, the milk started to flow and to increase. It is beautiful to see how they grow and grow only with one’s milk.” Caserío de Panecillo, town in Yapatera, Piura Region. October 2015

Jackelin Huaranca Huarcaya (18) with her baby Ashley Yurika, 3 months old. This young and new mother describes how the first days of breastfeeding were made difficult by lack of information and the pain she felt after birth. Time and experience have helped her feel more confident in her breastfeeding journey. “It is beautiful to look at her while she is breastfeeding and feel that she only needs my milk to stay healthy.” Central Market in Abancay, Apurímac Region. November 2015

Rocío del Pilar López Machoa (26) has four children. The youngest is Rafael, who is four months old. The two oldest, now 9 and 5, breastfed for nearly a year and a half. The daughter who is now one year and eight months did not have that luck. “When I became pregnant with Rafael, my daughter was only six months old and I had to take her milk away because I was told that otherwise I would hurt the child in me. She didn’t grow well, was thin and would get respiratory illnesses often, but she is now recovering.” Rafael, on the other hand, drinks a lot of breastmilk and is growing healthily. Belén, Maynas Province, Loreto Region. May 2016

Rocío del Carmen Zavaleta González (26) is mother of four children. Melanie is one year and five months old, the youngest, continues to receive the precious gift of breastfeeding. Even though Rocío feels she has less milk than in previous occasions, she continues. “I breastfed my first two until they were three years old. With the third, I was only able to breastfeed until the first birthday. Now I am trying to not let my milk dry up so that she is able to breastfeed for longer.” Caserío Manco Capac, Maynas Province, Loreto Region. May 2016

Ruth Madain Moreno Panduro (19) has two children— Paul, 4 years old, and David who is six months old. The three of them live with Ruth’s mother, Sonia, in one of the floating houses of the San Francisco shanty town. The little ones, constantly exposed to infections and colds due to the unhealthy conditions in the area (trash, drains and extreme humidity) have breastmilk as almost their only defense. Belén, Maynas Province, Loreto Region. May 2016

Sonia Briceño Cahuana (22), mother to Axel (3 years old) and Liam (7 months old). Liam continues to exclusively breastfeed. The family lives in Huayllabamba, a small town in Southern Peru. Sonia takes care of her children while her partner works in construction in the city. Town of Huayllabamba, Abancay Province, Apurímac Region. November 2015

Rosa Chistama Sangama (24) has five children. The youngest, Jessica, four months old, exclusively breastfeeds and on demand. She breastfed the other four, ages range from 7 to 2, for one year. “I have always had a lot of milk and now too. But Jessica does not breastfeed as much. When she is full a lot of milk continues to flow from my breasts.” Caserío Manco Capac, Maynas Province, Loreto Region. May 2016

Johana Robles (36) with Lucian, when he was two years old. “We continue with extended breastfeeding. We have been at it for already 3 years and 9 months. Despite the prejudices that exist in society, at the health centers, and primarily in my family, we have continued. I have the wonderful support from my husband and I know about the long list of benefits that come from extended breastfeeding, so I will wait until weaning comes naturally.” Costa Verde, Lima. October 2014

Katty Brown Miranda (32) and her child Tiago Alonso, 7 months old, at the door of her house in the shanty town of Canada, in Callao. Angie, who is 12 years old and the oldest daughter, observes her brother from inside. The baby has now started with solids but Katty continues to breastfeed him. “It is not easy being a mother. Sometimes one suffers a lot when your child is not well or you can’t give him everything you would like to see him happy.” Callao Province. July 2016

Libertad Mesco Huamán (27) is mother of 9 month old girl twins— Killary and Sharly. This young lady from Cusco also has a 10 year old girl. “With the help from the health center and thanks to the talks they gave us I have been able to breastfeed easier than the previous time. I have a lot of milk and I can breastfeed both girls at the same time. I am so happy because my girls are growing strong and healthy.” Markjo Community, Anta Province, Cusco Region. November 2015

Reyna Huamán Mamani (22) breastfeeds Yadiel, her 3 month old baby. Her oldest son is now four years old and he also breastfed. “I have always had good milk. My first child was always of good weight and height. I breastfed him until he was a year and a half.” Now with Yadiel she would like to continue breastfeeding until she is two years old. Markjo Community, Anta Province, Cusco Region. November 2015

Nancy Flores Rojas (26) has two children— an eight year old boy and an eight month old baby, Didi Anderson. Didi no longer exclusively breastfeeds. Nancy does not have as much milk as she did at the beginning and Didi’s increase in appetite demanded to complement his diet with new flavors. “He is eating other things now, but I know that breast milk is good for him and I will continue offering it to him.” Town of Auquibamba, Abancay Province, Apurímac Region. November 2015

Gisella Ballarta (36) is mother to two girls. With Dalia, she breastfed her until after her first birthday. “After a first stage that is always difficult, especially if it is your first, you reach a deep understanding with your baby. Breastfeeding is all about a mother’s perseverance. Sometimes we have to fight against society, which continues with absurd biases, and even with doctors, who recommend or give you cans of formula when you don’t have enough milk.” Parque de la Loma Amarila, Lima. November 2014

Asilia Reátegui Córdova (29) mother of three— 10 year old boy, 7 year old girl, and little Alissa Kristel of only 17 days. At the health center where she was attended to during her three pregnancies they recommended that she have a healthy diet to make sure her breastmilk was of good quality. Belén, Maynas Province, Loreto Region. May 2016

Romina Llomovatte Miranda was born in Buenos Aires in 1980. Her free and restless spirit from an early age has led her to travel endlessly and live in different cities around the world. A journalist and photographer by profession, she took her first steps under the watchful eyes of her artistic mother and her father, who is a photographer himself. She currently lives in Lima, Peru where she developed her photography project “Amamantar”, with the aim to promote and facilitate a conversation among society on the importance of exclusive and prolonged breastfeeding. This exhibition was inaugurated in August 2016 with the support of UNICEF Peru. For further information, please contact Romina Llomovatte at romilove@gmail.com or by visiting this Facebook page .

Stay Current: Research, happenings, and breastfeeding in the news

Research

- Barriers to Breastfeeding in Female Physicians, Breastfeeding Medicine, June 2018 Vol. 13, No. 5

- A Comparison of Factors Associated with Cessation of Exclusive Breastfeeding at 3 and 6 Months, September 2017 Vol. 12, No. 7

- Effect of a Pro-Breastfeeding Intervention on the Maintenance of Breastfeeding for 2 Years or More: Randomized Clinical Trial with Adolescent Mothers and Grandmothers, BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 2016 16:97

Happenings

- TOGETHER: Changing Your Community and the World, ILCA Annual Conference. Portland, USA 18 – 21 July 2018

- Breastfeeding, Research, and Infant Nurturing, LCANZ Breastfeeding Conference. Adelaide, South Australia, 5 – 6 October 2018

- 23rd Annual International Meeting of the Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine. San Francisco, USA November 14-17, 2018

- International Breastfeeding Conference, Healthy Children Project Inc. Florida, USA, January 15 – 18, 2019